Chiclero Consortium

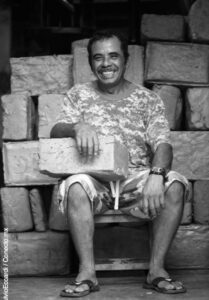

Looking at the chicleros, guardians of the rainforest, working is fascinating. Their relationship with the sapodilla tree is very close and respectful. They show than man and environment can interact and coexist.

Unlike other regions in southeastern Mexico, in the state of Quintana Roo the ownership and use of rainforests is in the hands of the farmers themselves, and the rainforest portion of each community is well defined. This made the farmers to become aware, as expressed by El Piporro, as we walk through the rainforest of the community of Tres Garantías, in the south of the state.

We are interested in protecting the rainforest. My grandfather was a chiclero, my father was one too, and I am still here in the same place, harvesting chicle. We have 44 thousand hectares of land and more than half is rainforest, what we call the permanent rainforest reserve. Cattle and agriculture are forbiden here. We get chicle and wood, but it is necessary to know how to do it.

This perspective has history behind. At the beginning of the 20th century, when foreign companies held the concession of these rainforests, farmers were hired as day laborers, both for cutting wood and for the extraction of chicle, and were paid extremely low wages. These companies did not care about the conservation of the rainforest, they never planted a tree or respected the rest time required by the sapodilla tree to extract the latex. Herman Konrad, a Canadian researcher who has studied the history of the region for several decades, calculates that at this time, in the state of Campeche, 20% of the trees could not recover, and between 1929 and 1930 up to a million of them disappeared. The old chiclero camps were the ones that gave birth to the new rainforest communities, which currently protect the main rainforest production reserves of the Yucatan Peninsula. In the 1930s, concessions were withdrawn and the ownership transferred to local communities. This change brought immediate positive results to the standard of living of the farmers, the income from the sale of chicle increased 300 percent and small settlements were formed where the population was concentrated.

In addition, schools and sanitary brigades were created, and they finally got running water services. In a few years the communities began to take over the entire chicle production, and that is how the first cooperative of producers was born.

However, mainly due to the fall in the demand for natural gum in the international market, this activity suffered a serious deterioration: of the 20 thousand chicleros that existed in 1942, the number fell to only one thousand in 1994.

Faced with this crisis, that same year in Quintana Roo a process of restructuring the activity began and the Chiclero Pilot Plan was created. The plan was developed based on direct consultation with producers and its objective has been to promote a new model of productive and commercial organization.

In 2003, the Chiclero Consortium was established as an integrating social company as a result of the merger of cooperative and rural production companies in the states of Quintana Roo and Campeche.

"We have managed to establish a balance between the sale price and production costs," says Manuel Aldrete, executive director of the consortium, "with a more equitable distribution of benefits and a greater participation of the producers in decision-making."

After four years of research funded mainly by its own resources, the consortium experimentally obtained six different formulas for the production of gum base and chewing gum. In early 2007, the consortium installed a pilot factory for the production of chewing gum, and managed to adjust the formulation to produce, at the artisanal level, a gum that contains at least 40% certified organic latex, mixed with aromas, flavors, and natural additives, thus consolidating a process of appropriation of a natural resource that has been commercialized for a hundred years as raw material.

The Chiclero Consortium, which manages production, logistics, trade, and finance, has shown that it is possible to make a sustainable harvest of the chicle sap, make Chicza and build a profitable business. Five years after taking the road to increase the value and transform the raw material of the chicle into chewing gum, courage and perseverance paid off: nowadays, this product means an income six times higher for a chiclero than it used to be. Every person who chews a Chicza tablet anywhere in the world, will be contributing directly and personally to the well-being of chicle producers from the rainforests of southern Mexico and keeping the Maya Rainforest alive.

The History

It is not known for sure if the ancient Mayans chewed gum, but surely the Mexicas did. What is known is that you could spot "streetwalkers" because they used to chew gum in the streets; also, children were given it to clean their teeth.

It is said that the American Thomas Adams, having failed in his attempt to vulcanize latex to replace rubber--a job that Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna had entrusted to him--had the brilliant idea of cooking latex and adding flavorings and sugar to sell it. This was the first successful attempt at commercialization of what we now know as chewing gum. But it was not until World War II broke out that American soldiers, who used to chew gum to relax, spread it to all corners of the world. Latex extraction reached its maximum level when in 1943 Mexico exported 8,165 tons of natural chicle based gum to the United States.

After the war, synthetic substitutes of petrochemical origin were discovered, because of this, the exploitation of chicle declined dramatically and only a few companies continued to use natural chewing gum. The Asian market was a strong consumer of the base gum produced by the United States, and with the emergence of synthetics, it was faced with the need to develop its own chewing gum formulas based on natural chicle, and turned its gaze towards the Gran Petén Rainforest.

Comments